West Down - North Devon village community website

History of West Down

Author

I am still a newcomer to the Parish of West Down, having only lived at Buttercombe since 1999. As an avid family historian, the history we inherit has always had a fascination for me, and this beautiful area of North Devon, in it’s quiet and peaceful journey through the years, has much to offer us. I do hope, whether as a resident or a visitor, that you find these pages interesting.

Please do send me your own memories, stories and corrections so that we can build a complete picture of the history of West Down:

Tony Stafford, Scrumpy Cottage, Buttercombe Barton Tel: 07866 804788 Email: toestafford@gmail.com.

I am indebted to Margaret Thomas, a “proper” villager; who published an absorbing history of West Down in 1995. Sadly the book is no longer in print. She has, however, generously allowed me to quote from her book which included the autobiography of William Facey. Many other village residents at that time made contributions, particularly those of the late Annie Chugg of Cheglinch. This is Margaret’s preface entitled Memories from an essay written for a Woman’s Institute monthly meeting competition in 1960.

Memories

I Remember …

Memories are always with us but do we fully realise how our lives would be if we could not recall any of the events of the past, sometimes it is not until we pause to think, that we fully appreciate how empty our lives would be if we could not recall any of these past times.

Firstly, there are the memories of the great occasions in our lives; the first day at school, some special achievement or perhaps the birth of a son or daughter or other special event.

The memories of a holiday last long after we return to our homes, the enjoyment of a happy time can last as long as the memory remains.

Secondly, there are little everyday things that bring back thoughts of happenings which were not very important in themselves, but will never be forgotten. A tune that reminds us of our school days, the smell of wild mint turns our minds to the harvest field where the corn has just been cut. The sight of falling snowflakes may still bring back some of the feeling of excitement we felt as children, when the prospect of a heavy fall of snow seemed to be one of our greatest desires. However as one grows older that particular joy does not last as long as in years past.

In winter when the days are up their shortest, and the weather is as depressing as can be, it is the recollection of the warmth of glorious summer days that are gone that keep our spirits up, and gives us hope and the sure knowledge that spring will come again.

Thirdly, there will be the sad memories, remembering the disappointments we have had; more often than not, on reflection, we are able to see some good has come of even the greatest sorrow. When we think of the loved ones now gone, let us honour their memory as we remember them.”

Timeline

1272 Gervaise de Crediton was the first recorded name of the Vicars of St Calixtus.

1343 A monument to the memory of Sir John Stowford, a justice of the Common Pleas, was erected in the Church.

1583 The parish register dates from this year.

1672 A cottage, three garden plots and a 3 acre field were purchased for the village poor with £20 left by John Eyre; together with the interest of another £40 left by the same donor. The cottage was sold to John Chugg in 1868 and the proceeds of £180 were invested to produce a distribution which in 1904 was 2s3d for 42 recipients. The “Poor Lands” Charity existed until 1985.

1678 26 parishioners contribute a total of £6.4s.0d to the rebuilding of St Paul’s Cathedral.

1687 Twitchen farmhouse was built.

1698 First recorded iron ore mining in the Parish.

1711 The Church tower was demolished and rebuilt the following year. Sir Nicholas Hooper of Fullabrook contributed £21 to the cost and also presented the clock and its bells.

1829 The Congregational Chapel was built. The building was demolished in 1985 with a move to the Sunday School building and the Chapel finally closed in 1995.

1850 For teaching six poor children, a schoolmistress has £40 a year from Mrs. Newcommen’s Charity.

1860 A number of mines producing mainly manganese were opened nearby with some iron ore mined in Spreacombe. Some of the terrace cottages in the village built to house the miners date from that period.

1871 There were 492 inhabitants (249 males, 243 females), living in 110 houses, on 4050 acres of land, including the small hamlets of Willingcott, Dean, Bradwell Mill, and Cheglinch, and the straggling farms of Trimstone, Stowford Barton, Buttercombe, and Aylescott.

1874 The Church was thoroughly restored.

In the same year, the Ilfracombe branch of the London & South Western Railway (LSWR) from Barnstaple was opened as a single-track line. It had one of the steepest gradients in the country.

1889 The new railway line to Ilfracombe was sufficiently popular that it needed to be upgraded to double-track.

1947 Mains water arrived in the village.

1953 Foxhunter’s Garage was built.

1954 Mains electricity and gas came to West Down in time for Christmas.

1957 The Parish Hall opened.

1970 Thanks to Dr Beeching, the Ilfracombe railway line closed despite nearly a century of bringing much needed revenue into this remote corner of the county.

1975 Mullacott Industrial estate opened.

1994 During the late spring a number of lambs were reported killed or lost, and early one morning the infamous Black Beast of Exmoor was allegedly sighted in the West Down Hill area and also at the Hidden Valley Caravan Park.

2011 The Fullabrook wind farm of 22 turbines became fully operational.

Early history

Between Mullacott Cross and West Down on the Hoar Down road is a field about 800 feet high where there are burial mounds dating back some 2,000 years. They are hollow inside with stone ditch work and contained earthernware vases in which charred bones had been placed.

West Down was known as the Manor of Dune and was held by Algar prior to the Norman Conquest.

In the Domesday Book of 1086 it was in the possession of Geoffrey de Mowbray, the Bishop of Coutances near Rouen, who had been awarded a considerable part of North Devon after 1066.

“It paid geld for half a hide. There is land for 5 ploughs. In demesne is 1 plough, and 4 slaves; and 15 villains and 3 bordars with 3 ploughs. there are 8 acres of meadow, and woodland 1 league long, and half a leagu

BORDAR – a cottager; a peasant of lower status than a villan

DESMESNE – land whose produce is devoted to the lord rather then his tenants.

GELD – the English land tax assessed on the hide

HIDE – the standard unit of assessment to tax, especially geld. Notionally the amount of land which would support a household; divided into four virgates

PLOUGH – the arable capacity of an estate in terms of the number of eight-ox plough-teams needed to work it.

VILLAN – a peasant of a higher economic status living in a village.

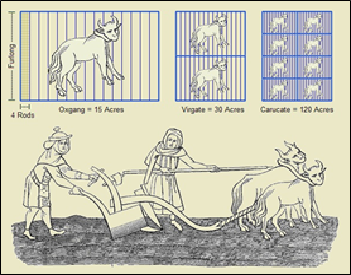

Farm-derived units of measurement:

The rod is a historical unit of length equal to 5½ yards. It may have originated from the typical length of a medieval ox-goad. There are 4 rods in one chain.

The furlong (meaning furrow length) was the distance a team of oxen could plough without resting. This was standardised to be exactly 40 rods or 10 chains.

An acre was the amount of land tillable by one man behind one ox in one day. Traditional acres were long and narrow due to the difficulty in turning the plough and the value of river front access.

An oxgang was the amount of land tillable by one ox in a ploughing season. This could vary from village to village, but was typically around 15 acres.

A virgate was the amount of land tillable by two oxen in a ploughing season.

A carucate was the amount of land tillable by a team of eight oxen in a ploughing season.

Tristram Risdon (c.1580–1640) was an English antiquarian and topographer, and the author of Survey of the County of Devon. He wrote of West Down that in ancient times it was the land of William de Columbers whose son, Sir Philip de Columbers married Eleanor (1285-1342) a daughter of Lord Martin, a Baron of Barnstaple and Dartington.

The Protestation Return of 1641/2

By the end of 1640, King Charles I had become very unpopular. Parliament forced him to make changes in the Constitution which gave them a bigger say in how the country was governed. From then on, Parliament was split into two factions – Royalists (Cavaliers) who supported the King and Parliamentarians (Roundheads) who wanted political and religious reform.

On 3 May 1641, every Member of the House of Commons was ordered to make a declaration of loyalty to the crown. This was ratified next day by the House of Lords. They called it their Protestation against ” an arbitrarie and tyrannical government” and another order was made that every Rector, Churchwarden and Overseer of the Poor had to appear in person before the JPs in their Hundred to make this Protestation Oath in person. It was to be a declaration of their belief in the” Protestant religion, allegiance to the King and support for the rights and privileges of Parliament”.

They then had to go back home to their own parish where any two of them were to require the same oath of allegiance from all males over the age of 18. The names of all who refused to make the oath were to be noted and assumed to be Catholics.

We have, in the Devon Protestation Returns, a set of amazing documents – something akin to a census even though no women or children are named. A transcription is available in the West Country Studies Library in Exeter.

The Protestation Returns are arranged by parish.

West Down belonged to the Hundred of Braunton

(The original spelling has been retained)

Walter Coates

John Hartnoll

Richard Peard

Lewis Dennis

Robert Hutchens

George Perrin

Nicholas Eyre

Francis Isaac, Gent

John Shepherd sen.

John Fosse

John Parminter

Richard Shepherd

Walter Fosse

Peter Parminter

(The above names are in the same hand, the following six are signatures)

Jacob Blaney – Clerk

John Haddon – Constable

William Fosse – Churchwarden

Peter Scampe – Churchwarden

John Robertes – Overseer

John Shepherd – Overseer

*For many centuries, Devon was divided into 32 administrative districts or Hundreds for land tax purpose.

Taken from the transcription by A. J. Howard published in 1973 which is available in the West Country Studies Library, Exeter. Courtesy Devon County Council

The Mining Industry

During the late 19th century there were over 57 mines in Devon which produced a variety of ore, including lead, manganese and occasionally silver. The manganese ore was used chiefly as an alloy with steel and with bronze and also in the process of colouring glass and paint production.

In the middle of Combe Martin are the remains of a mine first worked in the 13th century producing silver and lead which finally closed in 1880.

On the north of Halsinger Down the West Down Mine* had two passages 40 yards apart which commenced some 500 yards south east of Fullabrook Mill. There was another manganese mine in Snowball wood and another shaft near Pines Dean. They were worked from around 1875 for about 10 years, although annual production was low at some one hundred tons and with only about 10 employed at the Fullabrook mine.

*Also known as Huel Comfort, Little Comfort or West Down. Adits shafts and open-workings in valley 500 yds south-east of Fullabrook Mill. Sett also included Bakers Tenement lands, actually in West Down parish, north of the Fullabrook site. Manganese mine at work 1698, 1859-61 and 1872-84. Remains of dressing floor with water powered crushing mill.

Notable Village Buildings

St Calixtus Church

Please refer to the History of the Church under St Calixtus Church in “Organisations”.

The Manor House

The Manor house adjoining the church, which is mentioned in the Domesday book, would probably have been the original Vicarage although buildings of that era would be, by now, largely rebuilt, and there is no firm evidence available to give proof to this supposition.

The Old Vicarage in West Down

The oldest available documents relating to the Vicarage refer to the building on the square which was the residence of the Vicars of West Down until 1953. The following is from a document which appears to be signed Richard Chastie, who was Vicar from 1583 to 1616. The original is in the Devon record office in Exeter.

“Westdowne. The Glebe belonginge to vicarage, wher are my Lord Bisshopp is Patron conteynes one acre of lande or very neare thereabouts.

It hath vicarage howses on the west side of the Churchyard, one little orchard joyning to the houses of the vicarage on the north and west side. It has one halfe acre of ground, bounded on the north side with the lands of Peter Cotes and on the west side with the lands of Richard Peard, on the south the high way. Implements it has none.”

Another description dated March 22nd. 1679 gives some idea of the interior of the building consisting of “a hall earth ffloor’d” with a “little parlour also earth ffloor’d” also a kitchen and cellar both “earth ffloor’d”

The present house must have replaced the old building as the same site was owned by the diocese. The Grade 2 listing confirms that the “House, formerly vicarage, but probably originally a farmhouse with C17 origins, heightened and remodelled c.1820 when new front range added. “

However writing on the back of a skirting board indicated the front wing was built by “John Morris of South Molton in 1809”.

Village people in 1850

In the parish were 637 persons living on just over 4,000 acres of land. The estates around the village were owned by the Langdon, Parminter, Griffiths, Coats, and other families whilst Anthony Loveland, Esq., was lord of the manor of Bradwell and Dr. Yeo, lord of the manor of Stowford. The vicar was the Rev. H.J. Drury.

Hugh Acland was the landlord of the King’s Arms and John Davis owned the Blue Anchor. Other unnamed beer houses were run by Richard Collings and John and William Phillips.

Mary Phillips was the schoolmistress and John King owned the bakery and a shop. John Pile had another shop and William Setters was a grocer. George Collings and William Lewis were shoemakers, whilst there appears to have been five tailors – George Cornish, Henry Phillips, James Scamp, William Setters and William Vicary. Corn millers were William Thomas and George Phillips at Bradwell.

John May was the saddler and the Phillips brothers; John, Thomas and William together with John Setters were the village carpenters.

Of course the majority of parishioners were concerned with agriculture and these were the recorded farmers in 1850 – John and Thomas Chugg, Elizabeth, John and Robert Coats, Richard Coles, James Dyer, John Gammon, John Geen, James Hartnoll, John Heddon, Jonathon Menhinniott, Thomas Parminter, Robert Tucker and John Verney with James Frost also farming at Willingcott and Thomas Slocombe at Stowford.

The Village at Work

In 1902 the following were running businesses in the parish: –

Lewis Collins – Mason; George Cornish – Dairyman; Henry Gammon – Carpenter; Edward Heard – Blacksmith; Mrs Ann King – Baker and Shopkeeper; Thomas Lewis – Shoemaker; John Phillips – Carpenter and Wheelwright; Robert Phillips – Bootmaker; Arthur Robbins – Mason; James Smale – Dairyman; Mark Smale – Stonemason; John Taylor – Blacksmith; John Tucker – Dairyman; William Turner – Stonemason; Richard Roach – Shopkeeper and Post Office; Mrs Prisilla White – Shopkeeper; Frederick Thomas – Miller; George Yeo – Miller.

The Cattle Fair

There used to be an annual cattle fair held every September, the week before Barnstaple fair. A considerable amount of livestock changed hands on these occasions. A pleasure fair was set up in the centre of the Village, complete with swing boats, stalls of Fairings and gingerbread for the children. The last of these fairs was held in 1887.

After this date, a monthly cattle auction was held in the field on which Thorn Park has now been built. The last of these auctions was held in 1948.

West Down – The 1914 to 1918 War Memorial

West Down War Memorial © Richard J. Brine

by Siegfried Sassoon

Squire nagged and bullied till I went to fight

(Under Lord Derby’s scheme). I died in hell –

(They called it Passchendaele); my wound was slight,

And I was hobbling back, and then a shell

Burst slick upon the duck-boards; so I fell

Into the bottomless mud, and lost the light.

In sermon-time, when Squire is in his pew,

He gives my gilded name a thoughtful stare;

For though low down upon the list, I’m there:

“In proud and glorious memory” – that’s my due.

Two bleeding years I fought in France for Squire;

I suffered anguish that he’s never guessed;

Once I came home on leave, and then went west.

What greater glory could a man desire?

“Lest We Forget”

Remembrance Day 11th November

Remembrance Day is a time for us to remember the people who gave their lives during times of war and conflict. But, it started life as a day to remember just those from the First World War, or Great War, which was seen as the defining moment of the 20th Century, one that coloured everything that came before and shadowed everything that followed.

S. W. ADAMS – 202694 Private Stanley Wood Adams of the 1st/6th Battalion, the Devonshire Regiment. Son of Henry and Jane Adams. Lived in Braunton but born in West Down in 1898. Died 24 November 1917 aged 19.

T. ADAMS – 11967 Private Thomas Adams of the 8th Battalion, the Devonshire Regiment. Son of Thomas and Annie Adams. Born in West Down in 1894. Died 25 September 1915 aged 21.

E. ANDERTON – Lieutenant Edward Anderton of the East Army Forces, Son of Edward Anderton; husband of Edith Anderton of Folkstone. Born in 1874, Died 30 November 1918 aged 44.

N. BIRCH – Pte Nelson Birch joined up to serve in the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry but was then medically examined. Son of James and Frances Birch of Dennis Cottages West Down; husband of Mary (née Loveridge). Born in North Devon in 1899. Died at home 2 April 1919 aged 20.

Nelson Birch never served in action because he was suffering from advanced TB when he enlisted. He was almost immediately medically discharged to his home in West Down where he died. His brother James served in the Ox and Bucks Light Infantry in France before being, medically discharged and he also died of TB. James was born in a caravan in Plymouth. Our thanks to the Romany Travellers Family History Society.

F.J. CHUGG – 345651 Lance Sergeant Frederick James Chugg of the 16th Battalion, the Devonshire Regiment (the Royal North Devon Hussars). He was the son of James and Julia Chugg of West Stowford. Born in West Down in 1893. Died of pneumonia 26 June 1918 aged 25.

J. HARRIS – 12288 Private James Harris of the 1st Regiment, the Devonshires. Nephew of Alfred and Zilah of the Post Office, West Down who seem to have brought him up. Born in Tiverton in 1895. Died 24 March 1918 aged 21 and buried Pont-D’Achelles Military Cemetery, Nieppe, near Armentierres.

G. KIFF – 7695 Private George Kiff of the 1st Battalion, the Devonshire Regiment. Husband of Mabel (formerly Kiff) of South Lambeth, London. Born in Ilfracombe in 1886. Died 21 September 1914 aged 28.

W. KIFF – 22100 Private William H. Kiff of the 11th Battalion, the Middlesex Regiment. Son of Alfred and Annie Kiff. Born in West Down in 1898. Died 8 October 1916 aged 18. Buried in West Down Churchyard.

G.L. PHILLIPS – 9221 Sergeant George Lamberton Phillips of the Army Headquarters Detachment, the Royal Engineers. Son of John and Frances Phillips of West Down; husband of Ida Phillips of Southampton; brother of Trevor (see below). Born in Swansea in 1879. Died 2 January 1917 aged 38.

R. PHILLIPS – 7685 Acting Corporal Robert Phillips of the 1st Battalion, the Rifle Brigade. Son of James and Mary Jane Phillips. Born in Exeter in the June Quarter of 1900. Died 10 May 1915 aged 15.*

* Very few checks were made to validate under-aged recruits

L. PHILLIPS – 2429 Private Trevor Llewellyn Phillips of the 28th Battalion, the Australian Infantry. Son of James and Frances Phillips; brother of George (see above). Born in West Down in 1893. Died between 3 and 6 November 1916 aged 23.

W.E. PHILLIPS – 426756 Private Walter Edward Phillips of the 10th Battalion, the London Regiment. Son of Anne Phillips (w). Born in West Down in 1877. Died 29 November 1918 aged 41.

F.T. PILE – 14986 Lance Sergeant Frederick James Chugg of the 10th Battalion, the Devonshire Regiment. Husband of Annie Pile of West Down. Born in West Down in 1883. Died 4 October 1916 at home aged 33.

M. ROACH – 1191 Lance Corporal Mervyn Roach of the 15th Battalion, the London Regiment. Brother of Alfred and his wife Zillah at the Post Office. Born in West Down in 1891. Died 23 December 1915 aged 24 and buried in the Bethune town cemetery. (See below for the Diary of Mervyn Roach).

J. ROBBINS – 1080 Private John Robbins of the Royal North Devon Hussars, the Household Cavalry. Son of Arthur and Harriet Robbins. Born in West Down in 1873. Died 5 November 1915 at Home aged 42.

S.J. STANBURY – 700327 Private Sydney James Stanbury of the Manitoba Regiment, the Canadian Infantry. Son of Adam and Amelia Stanbury; husband of Lulu Stanbury of Sterling, Illinois, USA. Born in Bickington in 1892. Died 9 October 1916 aged 24.

W.F. THOMAS – 345913 Private William Frederick Thomas of the 16th Battalion, the Devonshire Regiment. Son of Frederick and Alice Thomas. Born in West Down in 1896. Died 3 December 1917 aged 22.

E.J. TUCKER – 18358 Private Edward John Tucker of the 2nd Battalion, the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry. Son of Ernest and Bessie Tucker. Born in Helston, Cornwall in 1896. Died 3 May 1915 aged 20.

W.H. TUCKER – 29006 Private William Henry Tucker of the 9th Battalion, the Devonshire Regiment. Husband of Florence Tucker of 1 Croft Lea, Berrynarbor. Born in Ilfracombe in 1893. Died 12 March 1917 aged 24.

R. WHITE – G/92857 Private Richard White of the Devonshire Regiment; transferred as 448 of the Agricultural Labour Corps. Son of John & Ellem White. Born in Berrynabour in 1877. Died 21 February 1919 aged 43. Buried in West Down Churchyard.

(R.) J. WILLIAMS – 50161 Rifleman (Reginald) James Williams of the 12th Battalion, the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, the London Regiment. Son of Mary and the late Alexander Williams. Born in West Down in 1887. Died 9 August 1918 aged 31.

The Diary of Mervyn Roach

Mervyn Roach, the son of the late Richard & Eliza Roach, who ran the Post Office & General Stores in the village, he died on the 23rd December 1915 and is buried in the Commonwealth War Graves section of Bethune cemetery.

This diary is a record of daily life in France until he went on leave. He returned to the front but did not take up the diary again.

His name is on West Down war memorial and there is a memorial tablet on his parents’ grave in West Down churchyard. He was 25.

Please click on this link to see the website created by Toni Buchan http://civilserviceriflemanww1.uk/

Mervyn Roach was Toni Buchan’s grandfather’s half-brother. Toni was born in the village and lived here for many years in The Old Vicarage.

Village Stories

Bill Facey was born at Lower Twitchen in 1920 and and farmed in West Down for most of his life until his death in 1994. These are some of his recollections:-

Farming

In the 1920s the majority of the employment was on the farms around the district. Most employed six or seven men with often a young man living in, plus a servant girl working in the farmhouse. There were about 40 farms and holdings in the parish including three Manors and four Bartons. The Manor houses such as Trimstone provided at least a dozen jobs, being namely, Coachman, 2nd Coachman, a Gardener, two Cattlemen, a Shepherd, a Carpenter, a Mason and three or four others standing to work, as it was called, namely making hedges, carting muck, weeding corn, cutting weed and thistles, trimming hedges, carting and turning hay and corn; and thrashing the corn in winter with the old waterwheel in action.

Wages were low at this time, about 30 shillings per six-day week. Most of the farmworkers would fatten their own pig in the garden shed to provide meat; then killing it in November and salting the meat in the salter, for use during the rest of the winter.

Most farms carry on along the same lines, producing milk, beef, mutton, pork and poultry. The milk and poultry being mostly summer trade to supply the many holiday makers that come to Ilfracombe by train and by the pleasure boats from the Welsh coast.

A Ghostly Story

In the 1930s there was a strange thing that happened in the Manor House (sometime known as Barton Farm) near the church. Some visitors staying at the Manor were supposed to have seen a ghost who beckoned them down to some underground passages that run from the Manor House to the Church. There they saw a room of beautiful furniture with lovely carved legs to the tables and chairs and nuggets of gold lying around on the floor! The funny thing of it all was that they never brought any out as evidence of the event. It has been said that tunnels run from the church to some mine shafts a couple of miles away at Fullabrook Barton. I don’t know the truth of the tale but it was published in the London newspapers at the time.

I Spy

Before the last war a Russian couple moved into Gills Farm. They seemed a very strange pair, about 50 years in age. She was not seen very much but he used to go into the village shop each day and buy a newspaper and cigarettes; he would then go to the local pub opposite, buy a drink and hide behind the newspaper pretending to be reading but listening to anything that was being said.

He wore a heavy coat winter and summer, covering a belt that held a couple of revolvers and at times he would give a regular at the pub a drink or two to go into the field at the back and hold out the frying pan for firing practice. If anyone went to watch him he would threaten to shoot them.

He stayed until around 1939 and then did almost a moonlight flit overnight; some said he was a spy, – who knows? I never heard of anyone seeing or hearing from him again.

The Last Invasion of Britain

On 16 February 1797 a fleet of four French warships left Brest, bound for Wales and carrying 1,400 troops in a plan to create a revolution amongst the Celtic people.

They passed Ilfracombe on the 24th and as all the local men were away on active duty, the women of the area, including Mary Chugg of this parish, dressed in scarlet petticoats and paraded them on War Hill. The French fleet deceived by this strong show of force, turned away and eventually sailed into Fishguard in an abortive attack – this became known as “The last Invasion of Britain”.

from Annie Chugg’s History.

Pubs

The Crown Inn (once known as The Braunton Inn) used to host the annual “Tithe Dinner”, held in a large room where the farmers and others had a good meal of roast beef with apple pie and cream.

The New Inn (now Myrtle House) – closed during the First World war.

The Blue Anchor (now Rose Bank) – closed in 1907 when “a married woman” bought it: she was the wife of Alfred Roach, the grocer and postmaster and the grandmother of Toni Buchan.

The Foxhunter’s Inn (on the A361) – closed in 2014.

The King’s Arms (possibly Kingsley House) – closed in the late 19th century.

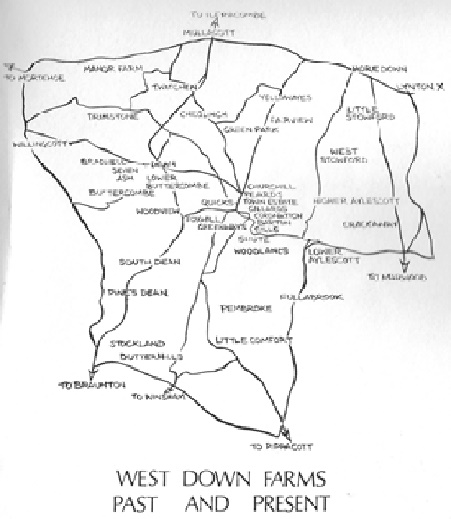

West Down Farms – Past and Present

After the Norman invasion, land throughout the country was distributed to the ruling nobles. Over the centuries, these large holdings were gradually split down through inheritance so that by the early 19th century most farmland was owned by a variety of absentee landlords and worked by tenant farmers.

Whilst most of the old farms within the parish 200 years ago are still in existence, the larger farms or Bartons* could be much reduced in size.

Many of the houses that the tenant farmers lived in then may have disappeared or being renovated, and the old stone cattle Barns converted into holiday cottages or residential homes.

Aylescott – The name for the farms we know as Aylescott has altered over the years. In 1086 it was Ailesvescotta, then Eilvescote and until 1489 it was Aylyscote. The names have changed and probably higher middle and lower are the same as self Wester and Easter of the earlier years.

Barton Farm – sometimes known as the Manor House. During the 16th century there is evidence to suggest that the farm was occupied by the Eyre family, followed by the family of Francis Isaac – the Memorial in the church tells some of their family history.

Bradwell – early spellings are – Bradevilla 1086; Bradwell 1242; Bradwielle meaning broad stream.

The Manor of Bradwell is mentioned in the Domesday book, the Lord of the Manor** being William de Pyne who was also associated with Pines Dean. During the reign of Edward the Confessor it was held by Edrick and it belongs to Ralph de Limesei in 1068. Gathered around the mill, it was almost certainly a larger centre or population long ago.

Buttercombe Barton is alleged to have been in existence at the time of the Norman invasion in 1066, and was probably included in the Hundred of Mortehoe, although individual houses are not mentioned in the Domesday Book. Before 1765 and presumably to 1850 the estate was owned by the Earl of Oxford and his descendants, particularly Margaret, Countess of Oxford who was the richest woman in Great Britain of her time. In 1850, the Great Tithes of Buttercombe were owned by John Langdon of London.

The farm was later owned by William Hole of Tiverton, succeeded by his son, Robert who was resident. The east window of the church of St. Calixtus in West Down has a triplet representing The Crucifixion by Mr W.H.Dixon in memory of Robert Hole Esq.

Cheglinch Hamlet was spelt “Chekelince” in 1330 and “Cheglinge” in 1612 and comprised the Manor and originally two other farms. There is an early record that Sir William Tracey owned all the land here before it was divided between neighbouring farms.

West Stowford mentioned in the Domesday Book, and was the home of Sir John Stowford (1290-1372) who was Chief Baron of the Exchequer in 1346. He built Pilton Causeway which links the towns of Barnstaple and Pilton, which before then were separated by the treacherous marshy ground in which flowed the tidal meanders of the small River Yeo. It is recounted that Stowford decided on building the causeway when on his way from his home, he found whilst fording the Yeo, the drowned bodies of a woman with her child. He is also believed to have contributed to the financing of the long-bridge in Barnstaple. The]original house has largely been rebuilt since the Judge resided there.

Trimstone Hamlet – Trimstone (spelt Trempeistan in 1238) was one of 11 Saxon ‘villein holdings’ of the manor of Bradwell almost 1000 years ago, when William the Conqueror made his sister’s son, Ralph de Limesy, his tenant-in-chief there. But it is thought that there was a settlement here well before that time. Trimstone is mentioned in the Domesday Book where it was held by Edric the Saxon before the Conquest and at that time there were 5 smallholders and 11 villagers. The Manor House dates back some three or four hundred years, was owned by the Langdon family until 1870.

*The word “Barton” is made up from the Early English ‚ “bere” which means “barley” and which can be extended to include “grain”; and from another old word, “tun” which had several meanings but in this context signified “enclosure”. Hence, “bere tun” became “barton”‚ and was interpreted as “barn” or “granary”. The meaning was expanded into “farm enclosure” and eventually came to refer to the whole acreage reserved to the Lord of the Manor.

**It is worth noting that in the context of a “manor” the title “lord” did not imply nobility (though some lords did hold high rank, but many were commoners) and meant simply “man in charge”. Today an equivalent meaning lies behind “landlord”.

Life on a Farm in Devon in the 1830s

Apprentices

Taken from a paper read in Totnes to the Devonshire Association by William Hornsey Gamlen in July 1880. William Gamlen lived at Brampford House, Brampford Speke. After he retired from his life as what might be called a “gentleman farmer”, he was appointed to the local bench of Magistrates, a position of which he was immensely proud. He filled his days keeping law and order in his neighbourhood and writing papers on farming-related topics for presentation to the Devonshire Association. He died in 1885 aged 71.

Farms and fields were usually not so large then as now and more of the work was done by the farmers, indoor servants and apprentices; every householder being obliged to take from one to six of these latter in proportion to his rental. These boys or girls were the children of persons receiving parish relief, or likely to require it, and were bound, at the age of seven or eight, to live with their master till they were twenty-one; he having to provide them with food and clothes, and medicine if required, and they worked without wages in return.

It frequently happened, when they were sixteen or eighteen years old, and had learned ploughing, hedging, reaping, mowing and threshing, which their masters were bound to teach them, that they ran away to try to get work for wages, and advertisements were often seen in the newspapers describing the fugitives and warning persons not to employ them. In other cases they misbehaved and got sent to prison for short terms, and so annoyed the master that he applied to the magistrates to cancel the indenture, after which they could do as they pleased.

Where the master could work with them and keep them till of age, they usually made good workmen, and often married and continued to work for him for many years. |t has been often observed that these workmen were far superior to their successors, who did not learn their work so thoroughly, nor take so much interest in it.

The boys’ dress was usually a fustian jacket and waistcoat, leather breeches and shoes – boots were never worn. Pieces of bag were tied between the ankles and knees as a sort of gaiter; these were called “kitty-bats” and were to keep the earth out of the shoes. These shoes, made of hide leather, were washed every Saturday night and well greased after being dried and in time became almost as stiff and hard as wood.”

“Kitty-bats” continued to be worn throughout the 19th century.

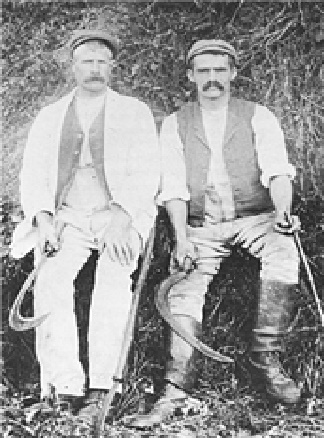

Both of these young men are wearing them although it is not so easy

to see this on the man on the left because they are canvas-coloured as

are his trousers. Those on his friend on the right are made of leather

which gave some protection against a miss-aimed swipe with a well

sharpened scythe as well as keeping mud out of his shoes.

An 1864 North Devon Labourer’s Fare:

Breakfast – Tea kettle broth (hot water poured on bread and flavoured with onions). Dinner – Bread (1861 4lb loaf 7½d) and hard cheese at 2d a pound with cider (sour). Supper – Potatoes or cabbage greased with a tiny bit of fat bacon. He seldom sees or smells butcher’s meat.

The cottager generally lacked fuel to make fire as Devon was far from coal supplies and wood was scarce and firing was not allowed except in the form of permission to grub up the roots of old hedges. Therefore, there was little heating and cooking.

At the age of 45 or 50, the peasant was usually found to be crippled up by rheumatism. Carpenters were traditionally also undertakers. Midwives had a very low status, and were commonly held to have been “dirty old hags” who more often than not hindered rather than helped. The midwives used much folklore and herbal remedies.

The Daily Grind

“The village tailor used to go to the farmhouse and make and mend the boys’ clothing with materials kept for the purpose, and received eight pence and sometimes a shilling a day and his food for doing this. He sat on the kitchen table at his work and kept the mistress employed in supplying his requirements of more cloth, thread, buttons etc. till her patience was well worn. On one occasion in hot weather, an apprentice girl whispered “Missus, Missus, the tailor is asleep!” and received for answer “Hush! for patience sake don’t wake him – I’ve had plague enough from him already. ” In some places the shoemaker went to the house and mended what required repair from a stock of leather kept for him. The apprentice girl milked and tended the pigs and calves; if these were too many, the boys helped her. She also helped to make butter, scald the milk* and make cheese, which was consumed in the house or sold for threw or four pence a pound, being so poor in quality that now it could scarcely be sold at all. The boys helped to feed and bed the horses and bullocks night and morning and while young, drove plough and assisted in any other work they were fit for.

They, and the servant man, had broth or milk with bread for breakfast a little before seven a.m and took some bread and cheese in a bag to eat with their cider for “forenoons” about 10.30. The whole family dined in the kitchen together at one o’clock, the man and boys at the lower end of the long table using pewter plates or wooden trenchers; the master and his family at the other end using plain white earthenware. Cider or home-brewed ale was the usual drunk by all. In some places the apprentices were worked very hard, roughly treated and beaten for trifling faults or awkwardness in doing their work. Teaching them to read and write was rarely thought of**.

Seven shillings*** a week were the usual wages for men with three pints of cider a day. In harvest time, food was given or extra pay in consideration of the longer hours of work, and generally grist corn was supplied at less than the market price of wheat, but often of very inferior quality. Sometimes the run of a pig in grass was added, or some ground allowed for growing potatoes.

For weeding corn, hay making, binding corn, digging turnips, picking stones, picking apples etc., women were paid eight pence a day, with one quart of cider. If not apprenticed, boys were paid sixpence a day for similar tasks or for minding cattle and sheep or scaring birds off growing crops. A fire in the hearth was universal so they were needed to make thorns and brambles into faggots which produced a blazing fire for drying clothes by or for baking.

The hay was all hand-made by women and boys, the men helping too after ending the mowing. Mowing was done by hand, with each man being expected to cut an acre a day. Neighbours helped each other, two or three sending their servants to help one and getting similar return from each other. In this way, fields were quickly cleared one after another.”

* Milk was scalded during the cream-making process.

** To read more about the treatment of apprentices, go to Mary Puddicombe’s Story.

*** It’s not easy to give an exact equivalent but using the year 1830 in conjunction with the National Archive’s Calculator, 7 shillings a week would equate to the purchasing power of around £15 today. For this a man was expected to work some 60 hours a week – a little less in winter. For a woman earning 8d per day, (in the summer, that would be for 10 to 12 hours work) her weekly wage would have been the equivalent of £1. 50 in 2010.

Snippets

The Naughty Wives of West Down

North Devon Journal of 31st January 1828

Petty Sessions, Castle Inn, Barnstaple, June 24th 1828

Jane Norman, Elizabeth Phillips, Jane Bale, and Mary Kieft, the wives of four labouring men were convicted of stealing fuel from Stockland Wood, in the parish of West Down, and fined 6d each, with 2s 6d expenses. The Bench admonished them not to place themselves in the like situation again, as in all probability, the utmost penalty of the law (viz. two months imprisonment) would be visited upon them.

Fifth Time Lucky

NDJ of 17.11.1842

At Westdown, yesterday, Mr William Heddon, mason, of Braunton, to Widow Phillips, of Westdown. This is the fifth time the fortunate swain (who is not yet 60) has paid his devoirs at the hymeneal altar, and as he makes it a sine qua non to obtain a fortune with each, he is likely to become a rich man in time. The bells of his parish rang merrily to greet him on the auspicious event.